On tigers in Japanese art. Or A different kind of Tiger King.

Tigers, and feline types in general, have a long history of representation in Chinese, Korean and Japanese art. As they have in the West, to be frank. I do think, however, that there is something special worth focusing on in the Far Eastern variations. I would love to bring you along with me, through some peculiar tigers of Japanese art, all the way through my favorite one, by an incredibly, and rightfully so, famous master.

Almost exactly three years ago I spent one of the most fun and pleasant spring days of my life in the breathtaking Tenryūji temple in Kyōto. It was a sort of a school trip and our guide was our teacher of Japanese language: Tokyo native, but obviously passionate about the ancient roots of her country, often said to be preserved in the ancient capital of Kyōto. Between the marvelous things we were shown, I still vividly remember a set of profusely decorated fusuma (wooden panels). Our teacher urged us to comment on it. What do they represent? What feelings was the artist trying to convey? The second question proved itself to be easier to answer to. Strength, determination, maybe anger? The eyes of these potent figures were certainly telling. As for the first question, what exactly we were looking at was not as clear. The animals scattered across the fusuma, some lying on top of rocks, others slithering menacingly toward an invisible pray, could have been any type of feline. Our teacher understood our perplexity. “They are supposed to be lions. You can see some have a mane-like fur around their necks. You are right, though. They are not very realistic!”

If we take closeness to the real world as our only parameter to judge the quality and importance of a work of art, we might find most tiger portrayed by Japanese artists to be a bit, well… questionable. Hopefully, though, in the last century we have learned to look beyond sterile likeliness; how to appreciate the eloquence with which some of these tigers exude sometimes strength and sometimes calm. In Western art, trying to match the original was always the ultimate goal, but for most Eastern artists, techniques such as perspective and chiaroscuro did not help much in their artistic endeavors. It just was not what they were trying to achieve. As I said, the lions depicted on the fusuma in Tenryūji could have been tigers or pumas, but their force was unmistakably understood. In Chinese and Korean art and architecture we often find the so-called shi, which are effectively a barely recognizable rendition of a lion, at the entrance of sacred places. The ever present strong and unbreakable spirit and pride of the animal is the only truly important feature, it seems.

It is often said that at the end of the XIX century the Western manuals of biology and zoology taught some Japanese artists how to depict nature in a more realistic way. This doesn’t mean that incredibly detailed and almost photorealistic depiction of animals was not already well established. This, however, was a teaching that came mostly from Chinese masters, not from Western practices. Just think about the astonishing, almost too perfect roosters painted by Itō Jakuchū (1716–1800). Very realistic tigers are not as numerous. Overtly expressive, moving, thought-provoking tigers, on the other hand, were quite common.

Living, breathing tigers were not an ordinary sight in Japan, but they were in China. Most Japanese artists would copy the mainland’s examples, but had never encountered a tiger in their life. Kanō Tsunenobu (1636–1713) represents a wide eyed tiger, with a sinuous body peeking through some bamboo stems. The head could more fittingly belong to a jaguar, but the rest of the body does bear the typical stripes. It’s a curious, tense animal. Hirowatari Koshu (1737–1784), Nagasaki native, draws a suspicious, cautious tiger. It is not aggressive. Its mouth is closed and its paws remind the viewer more of a house cat’s than a fearsome beast’s.

Another master of the sumie (ink) technique (among other things), Tawayara Sōtatsu, (1570–1640) has chosen the tiger for one of his works. This time, captured in a delicate, docile moment. It is licking its paw, and its eyes appear to be closed, or maybe just relaxed: a detail masterfully rendered with two minuscule brushstrokes. No claws are visible. This domestic quality, found in more than one instance, might come from the fact that the live models, that would usually stand in instead of a tiger, were common house cats. In some cases the tiger is used to symbolize the concept of yin, feminine and unstable, in opposition to a dragon that stands for the more beneficial yang. Especially in grandiose paintings in which they engage in strenuous fights. The tiger is also a guardian and predator of evil spirits and bad fortune. Sōtatsu, however, seems more preoccupied with the tiger as a real animal, bearer of feelings and a personality.

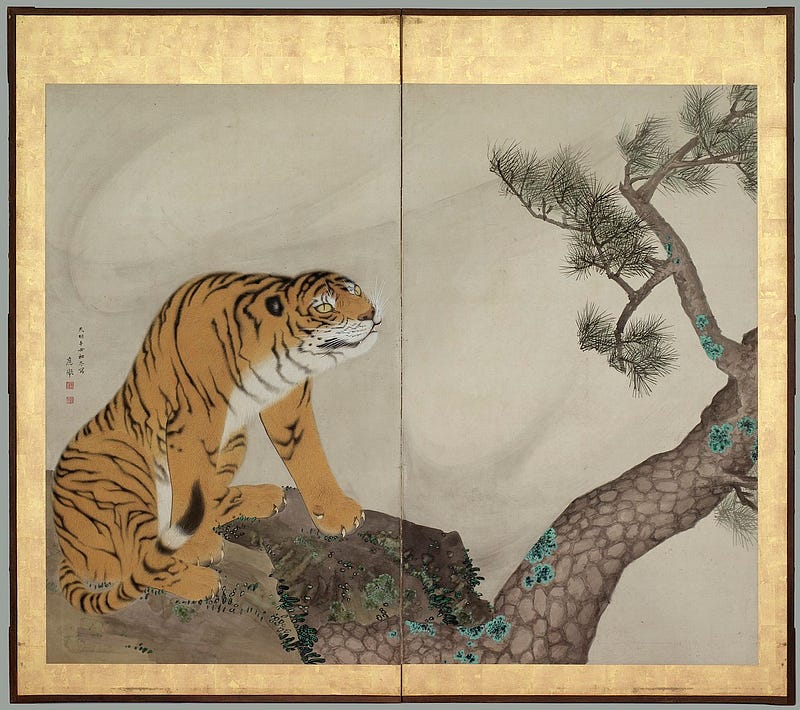

In a staggeringly colorful Maruyama Ōkyo’s (1733–1795) version of 1781 we can see a very improbable feature that was present in many paintings that represented tigers at that time: the reptile-like pupil. It might not be akin to reality, but it contributes to the intimidating attitude of the animal. Or to its firm spirit. Seated on a beautifully accurate mossy branch, this is the portrait of a lonely, valiant beast. But also the allegory of independent thinking and fortitude. Tigers are the protagonist of another one of his masterpieces. On a sunny gold scenery, three adult tigers and a cub are arranged in various poses. The central one is a mother, who is helping her cub cross a river by delicately holding it in her mouth. The other two are engaged in very elastic, appropriately feline postures. One is licking its paw while the other seems to be looking at the busy mother, intrigued. The scene is taken from a riddle that asks how many trips will the mother have to take to ensure that the one naughty cub doesn’t hurt the others when they are left by themselves. Maruyama Ōkyo expertly leaves tiny, barely perceivable lines of gold to signify the river, and the detailed animals seem to float, as objects do in many fusuma with a gold leaf background. It is a pleasant, homey scene, that might suggest the sense of familiarity, of similarity between animal and human affections.

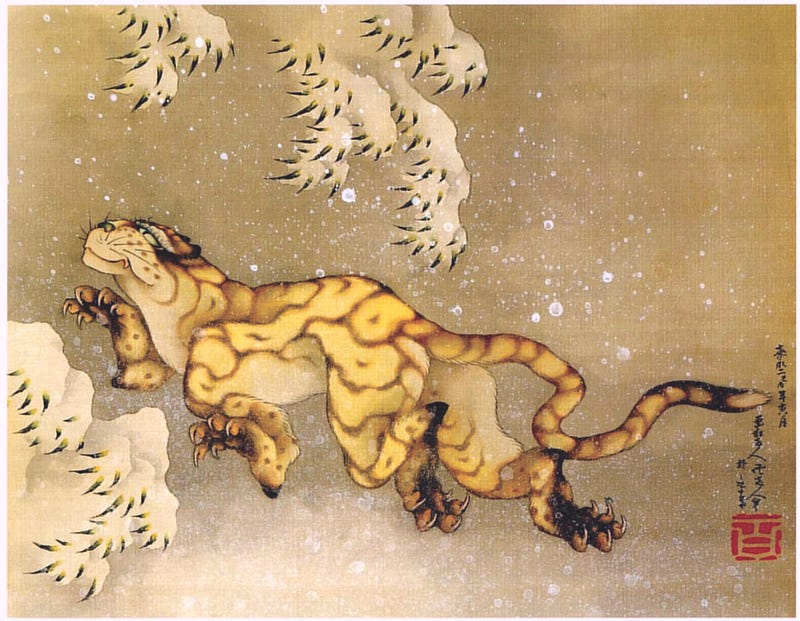

My favorite tiger, though, is probably Katsushika Hokusai’s (1760–1849) one. I think that the great master has achieved something much deeper and substantial than a representation of a tiger. Sure, we have seen other artists put their own personal spin on the subject. Every tiger seems to have a particular character and is often a symbol of fortitude and determination, of the struggle of motherhood or of spiritual honesty. Hokusai, however, has done something even greater: he has portrayed himself, his spirit, as a tiger. It is sad that the painting “Old tiger in the snow” of 1849 might be the very final masterpiece in a life devoted to art and enamored with the forms of the world. The old and ill master was forced to draw in bed near the end of his life. This did not stop him from creating some of his most inspired work. A kind of daily ritual for him was to draw a shishi (the Chinese shi, dog-lion creature). They never looked the same, and with them he explored many poses and expressions. A sort of amulet, to exorcise the fear of death. Many actually look a lot like our tiger. Almost like they were preparatory designs for the final masterpiece. The body of the animal stretches out along a straight, diagonal line. Its fur is not a tiger’s. It’s composed of vaguely circular, almost abstract shapes. The snow is made almost with a freeform, kind of dripping technique, and contrasts strongly with the precision of the animal’s form. The sharp claws are repeated in the pine needles, partially revealed by the snow. It’s jumping upwards, and its exaggeratedly long tail follows like the decorative strips of a kite. Its gaze is resolved, it doesn’t hesitate. It is, after all, an old tiger. It knows its role, what it’s meant to do and to be. It’s trying to reach something beyond the painting. It is Hokusai’s soul, launching towards the afterlife. It is his legacy, diving into immortality.