The minimal unearthliness of Rei Naito

Today, I would like to take you on a journey. We will follow a human life as it unfolds, along an ideal path from birth to death and even to the “other side”. Will you come along? I promise you are not going to regret it. I know a remarkable artist that can lead us. Rei Naito, who was born in Hiroshima in 1961 and has been preoccupied with life and its meaning since her first works.

We will start with birth. At the 47th Venice Biennale in 1997, Rei Naito filled the Japanese pavilion with an installation that embraced who walked in, surrounding them with a suffused light. It was called One Place on the Earth and it was an oval-shaped tent that symbolized the interior of a woman’s body. It’s a comforting and reassuring representation of the womb. The particular quality of her art is already visible in this work. The curator Fumio Nanjo calls it hakanasa. It evokes the Japanese ideal of beauty as ephemeral and transitory, typical of flowers and life in general (frequently at the core of Naito’s work).

On Teshima island, you can explore Ryue Nishizawa’s artificial cave. Light comes in through two openings in the ceiling and creates a contemplative and calming atmosphere. Here a subdued contribution of Naito can be seen by an attentive eye. Her presence is always subtle and perfectly integrated with its surroundings. Tiny droplets of water emerge from an underground spring through small holes in the ground. Following the inclination of the floor, they seem to race, overtaking each other and occasionally colliding and combining in larger puddles. Dancing in unexpected patterns, they finally gather and are drained through other holes. This splendid movement makes the water look lively, and not only a source of life but alive itself. The windows of the cave allow the visitor to enjoy the view of the greenery of the island and let diverse insects roam in and out of the architecture. The whole environment is a quiet and understated celebration of life. Over the years, Naito has kept enquiring about the origin of life and asking herself: “Is our existence on Earth a blessing in itself?”. This work explores this question: a possible answer resides in the surprised expressions of the people that see water being born, sprouting into life directly from the ground. The title of this work, Matrix, is meaningful in this sense: the Latin root of the word means “mother”, “womb”. Even the Japanese translation bokei 母型 has the kanji of “mother” in it. Another very delicate variation is Tama/Anima (Please Breathe Life Into Me). It consists of a rail with water on it, that people are invited to blow on. The aim is to instill life in this inanimate, but potentially fecund element by altering its form and position.

Our journey takes us now to life itself, and the many ways in which Naito celebrates and investigates it. According to the artist, humans come through the matrix of nature to the world. Once there, their presence as newborns occupies a circle of the diameter of 78mm: it is roughly the area one takes up with their feet. Each individual should take good care of this sacred space they have been granted, because it is perfectly sufficient to lead a life. Naito has materialized this area in different ways: one of them is Grace, a smooth, milk-white marble disk placed on the ground. Another one is a glass jar filled to the brim with water. Again, the artist is trying to show us the physical space a human requires to be able to live, this time exaggerated by the impression of the uncontrollable nature of the liquid. Naito also often uses light to reveal with disarming simplicity her personal reality and her understanding of existence. Sometimes it takes the form of slight touches of color on a canvas.

Light envelopes us with grace, coming from nowhere, showering upon us unconditionally.

In the series Color beginning, she relies on the discrete power of light to show very faint pastel tints that seem to emerge right there and then, in front of our eyes. Light (or lack thereof ) has been used in Being Given as well. This installation used to be a house built originally a century ago in the Honmura district of Naoshima island. It is now part of an art project that aims to requalify the area by transforming some of the abandoned buildings into works of art. Being Given looks like a traditional Japanese house devoid of light. It has no windows. Just a narrow opening along the bottom of the walls from which sunlight seems eager to enter. The roof is supported by wooden pillars and in the very center of the floor, there is what looks like a circular irori (traditional Japanese fireplace). It can be experienced by one person at a time and it speaks of family, tradition, and everyday life in a mysterious and odd way.

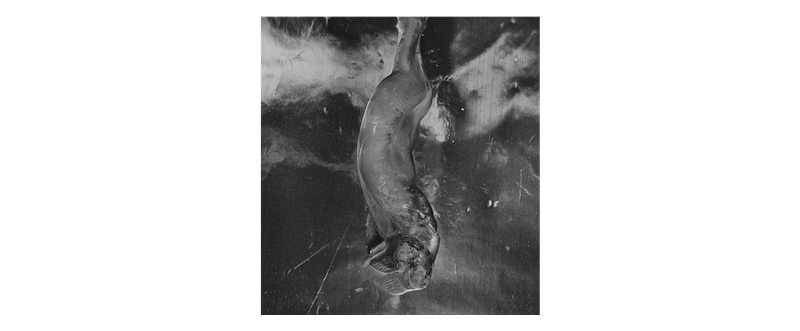

We are now moving toward a different realm, beyond life. As bleak as it may sound, I assure you Naito will be as delicate and hopeful as ever accompanying us to this last stop. After the Great East Japan earthquake of 2011, some humanoid figures started appearing, or so it seems, more and more frequently around Naito. She carves these hitogata from wood, like many people in history have done before her. It is apparently a quite common, natural thing to do, especially for the more spiritually gifted among us. They are stylized and have minimal features. Sometimes they are solitary individuals, while other times they form larger groups that symbolize humanity. Naito also never forgot her native land of Hiroshima and the pain it went through. In relation to both nuclear tragedies, with this almost obsessive repetition, she appears to be trying to repopulate the world, sadly deprived of those souls. In the exhibition Émotions de croire held in 2017 in Paris, she scattered on a table a number of these tiny people, each of them standing next to a broken, melted regular-sized bottle, almost like they are guarding these relics. These containers are now useless. They can no longer hold water like the glass jar from earlier. They can’t be carriers of life anymore. Nonetheless, hitogata protect them. The way in which they are deformed reminds strongly of the Melted bottle photographed by Shōmei Tōmatsu (1930–2012): confused, distorted, barely identifiable, but so grimly reminiscent of the bodies of the victims of the bomb.

The table is surrounded by fairy lights and decorated all around, like what happens to some trees and other natural things in Shinto religion, where they are enclosed by shimenawa, sacred ropes. Naito is well aware and proud of her roots in an animist culture and the capability of its symbols: a work simply named Balloon is a smokey grey balloon hung above an entrance door that in a fun, light way delimitates a special place where suddenly the air feels just different. The Parisian one is a minimal scene, a fantastic forest populated by figurines that remind me of the charming little forest spirits called kodama (you may have seen them in Princess Mononoke by Miyazaki). But it is also so rich in meaning. Can it be a sort of afterlife? This simple work is once again a gentle but powerful statement about humanity and the value of life or what it means to lose it:

The “human” is an existence that firmly believes that it sees hope.

These tiny souls are a touching testimony of people’s passage through this world. And a reminder, like many of Naito’s works, that we are inexplicably, beautifully, and desperately part of something greater.

I hope you enjoyed the trip and that it enticed you to continue the exploration of Rei Naito’s fantastic world.